Newhouse Dynasty's 20th-Century Media Conglomerate Hidden History Revisited (1)

"The same book also characterized the Samuel I. Newhouse Foundation as `a charity his [Samuel I. Newhouse I’s] lawyers had created as an additional tax dodge'...”

In 1962, Oregon’s then-U.S. Senator Wayne Morse argued that “The American people need to be warned before it is too late about the threat which is arising as a result of the monopolistic practices of the Newhouse interests.” Yet, historically, many 20th-century U.S. newspapers were still owned by the Newhouse interests as late as the early 1990s.

One reason neither 20th-century magazines like Parade and the Vogue/Conde’ Nast magazines (that were historically subsidiaries of the Newhouse Dynasty’s media conglomerate) nor the Newhouse Dynasty needed to worry, historically, about being satirized too much in many U.S. daily newspapers during the last decade of the 20th-century was that many U.S. daily legacy newspapers were then still owned by the Newhouse Dynasty’s Advance Publications holding company.

In the early 1990s, the fourth-largest newspaper chain in the U.S., for example, was then still owned by the Newhouse Dynasty; and over $1.7 billion [equal to around $3.7 billion in 2023] per year was taken in by the Newhouse family company from its 26 newspapers during the early 1990s.

The daily circulation of the Newhouse Dynasty’s newspapers exceeded 3 million in the early 1990s. And the following U.S. legacy newspapers were still all owned, historically, even in the first decade of the 21st-century, by the same media conglomerate which then still published and owned Parade and the Vogue/Conde’ Nast magazines: Newark Star-Ledger; Jersey City Journal; Trenton Times; Staten Island Advance; Syracuse Post-Standard; Portland Oregonian; Harrisburg Patriot/Patriot-News; Cleveland Plain-Dealer; Birmingham News; Huntsville Times/Huntsville News; New Orleans Times-Picayune; Springfield Union News/Republican; Ann Arbor News; Flint Journal; Grand Rapids Press; Kalamazoo Gazette; Bay City Times; Saginaw News; Jackson Citizen-Patriot; Muskegon Chronicle; and the Mississippi Press-Register.

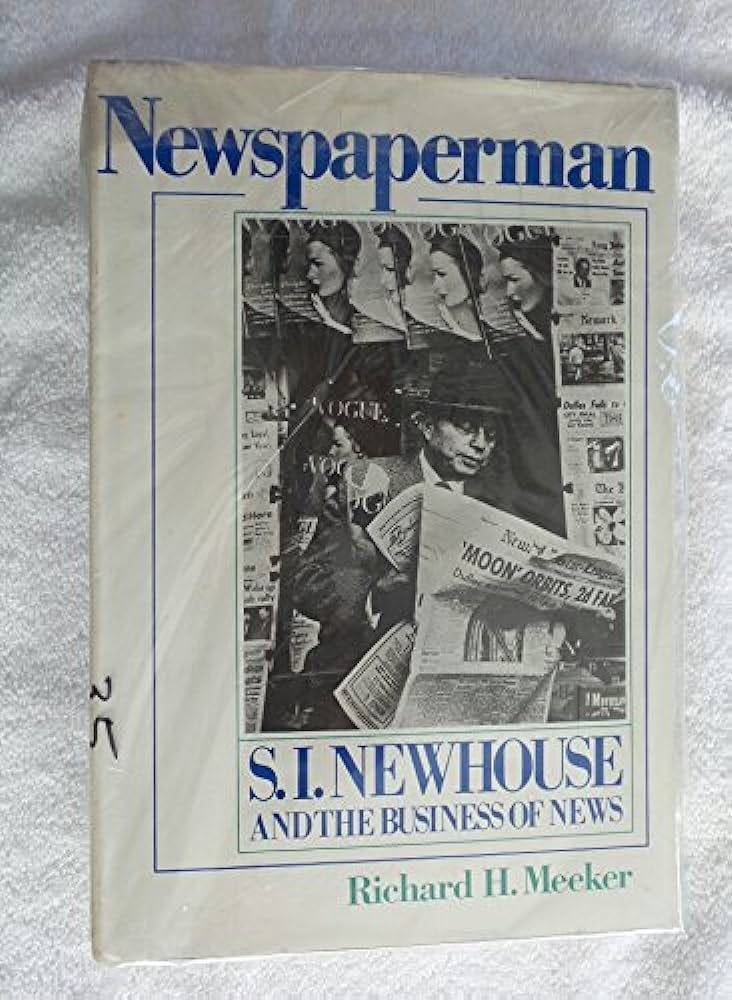

During the 1950s, Newhouse’s Newark Star-Ledger (whose circulation still exceeded, historically, 400,000 in the early 1990s) apparently agreed “to be used as a conduit for charges [Joe] McCarthy himself didn’t dare make public,” and “when certain of its syndicated columnists, Drew Pearson among them, began to attack McCarthy, the Ledger refused to print the revelations,” according to Newspaperman: S.I. Newhouse And The Business Of News by Richard Meeker.

Coincidentally, when a book critical of the Newhouse media conglomerate’s seemingly monopolistic practices, Newhouse, Newspapers, Nuisances: Highlights In The Growth Of A Communications Empire by John Lent, was published in the early 1960s, none of the newspapers which were part of the Newhouse newspaper chain printed a review of the book.

Newhouse newspapers were not particularly known for being examples of quality journalism during the 20th-century. Indeed, in 1964, Newspaper Guild Vice-President William Farson made, in reference to Samuel Newhouse I, the following comment:

“More people jump on Newhouse than other monopolists because he has a history of putting out poor newspapers. He wants no competition because if he had to compete, he couldn’t afford to put out a poor paper, and in the process he wouldn’t make as much money.”

And when More magazine—a magazine not then owned by the Newhouse Dynasty—“compiled a list of the 10 worst big-circulation daily newspapers in America” in the 1970s “three of Newhouse’s newspapers were on it,” according to the Newspaperman book.

But ever since Samuel Newhouse I had started working as an office-boy, bookkeeper and rent-collector in New Jersey Democratic Party machine politician, Bayonne Times owner and Judge Hyman Lazarus’s law office in 1908, the Newhouse family had, historically, shown a remarkable ability to accumulate more money, more swiftly, than most families who had gotten involved in the U.S. media world during the 20th-century.

By the time Samuel Newhouse I was 21 in 1916, he was earning around $30,000 [equal to around $845,000 in 2023] per year and had been given 25 percent ownership of the Bayonne Times by his boss, Judge Lazarus, for his loyal service. By 1922, Newhouse had saved up enough money to purchase the Staten Island Advance in partnership with Judge Lazarus. And a few years later, when his original partner, Judge Lazarus, died in 1924, Newhouse also had enough money to buy up the Lazarus family’s share of Staten Island Advance stock.

During the 1920s, the Newhouse family also then had enough money to loan the money to Henry Garfinkle which enabled Garfinkle to open newsstands that were quite good at selling the Newhouse family’s Staten Island Advance at the St. George’s Ferry Terminal on Staten Island, as well as to open newsstands throughout Manhattan, at LaGuardia Airport, at Newark Airport and at the Port Authority Bus Terminal (the world’s then-largest and most historically lucrative newsstand)—which also sold other Newhouse publications quite well throughout the 20th-century.

During the 1930s Depression, the Newhouse family still had enough money to buy the Long Island Press newspaper in Jamaica, Queens and the previously competing Long Island Star, North Shore Journal and Nassau Journal newspapers, as well as the Newark Ledger, the Newark Star and newspapers in Syracuse. At the Long Island Press during the 1930s—where the Newhouse family was paying its then non-unionized newsroom employees only 33 percent of what unionized New York Times and New York Daily News employees were then earning for similar work—Samuel Newhouse I’s individual annual salary from that newspaper was more than the total of all the annual salaries paid to the Newhouse family’s 65 non-unionized newsroom employees there, at that time..

By the time the Newhouse family somehow found the capital, historically, to purchase more newspapers in Syracuse, Jersey City and Harrisburg in the 1940s and in St. Louis, Oregon and Alabama in the 1950s, some people began to wonder how the Newhouse family had obtained so much money. And by the time the Newhouse family—whose wealth approached $200 million [equal to around $2.1 billion in 2023] in the late 1950s—laid down its cash to gobble up Vogue and the other Conde’ Nast magazines, more suspicions about the Newhouse family’s source of wealth had developed. As the book Newspaperman by Richard Meeker recalled:

“Newspaper analysts were so suspicious of the source of Newhouse’s funds that they discussed openly the possibility that he was laundering money…Some went so far as to suggest that his newspaper operations had been used as a front for the notorious Reinfeld mob, a group of booze-peddling hoodlums, whose boss had made millions during prohibition.”

One way the Newhouse family apparently was able to, historically, accumulate so much money so rapidly during the 20th Century was by hiring accountants and lawyers who figured out unique ways for the Newhouse Dynasty to avoid paying a fair share of taxes on their rapidly growing family wealth. As Newspaperman reported:

“`They played every tax game there was,’ recalled one man who once served as publisher for several Newhouse newspapers. That meant that every cost that could conceivably be written off as a business deduction was, that assets were depreciated as rapidly as possible, and that new acquisitions were `written up’ as high as the law allowed…Where Newhouse developed a special advantage was in the way he avoided paying taxes for the profits that remained to him after the payment of corporate taxes…

“Thanks to an ingenious device created by his accountant, Louis Glickman, and implemented by his attorney, Charles Goldman, Newhouse was able to avoid paying taxes on accumulated earnings and, thus, to multiply the value of his earnings several times. Doing so involved the creation of a special corporate structure for the various newspapers…Because the Goldman-Glickman construct kept the various enterprises separate—for tax purposes at least—each could claim the right to its own surplus. Taken together, the accumulation that resulted was many times what the IRS would have allowed had Newhouse simply treated all of his operations as a single corporation.”

The same book also characterized the Samuel I. Newhouse Foundation as “a charity his [Samuel I. Newhouse I’s] lawyers had created as an additional tax dodge” and charged that Newhouse Foundation funds were used by the Newhouse family to finance its $18 million [equal to $206 million in 2023] purchase of Alabama’s Birmingham News in 1955.

After Samuel Newhouse I died in 1979, his two sons, S.I. Newhouse, Jr. and Donald Newhouse, were also accused, historically, of tax evasion by the IRS during the 1980s.

Six months after their father’s death, S.I. Newhouse, Jr. and Donald Newhouse valued Samuel Newhouse I’s estate at $181.9 million, for example, and filed a tax return which claimed they owed $48.7 million in inheritance taxes.

In 1983, however, the IRS informed the Newhouse brothers that their father’s estate “was worth an estimated $1.2 billion [equal to around $4.4 billion in 2023], and thus the tax as computed was deficient by more than $609 million [equal to around $2.2 billion in 2023]” and “the government tacked on a 50 percent penalty ($304 million [equal to around $937 million in 2023] and change) for civil fraud,” according to the March 13, 1989 issue of The Nation magazine.

Although the IRS dropped its tax fraud charge against the Newhouse Dynasty later in the 1980s, it increased its tax delinquency bill for the Newhouse family to $1.2 billion [equal to around $3.7 billion in 2023], since it claimed the Newhouse estate was actually worth $2.2 billion [equal to around $8.2 billion in 2023]—not $1.2 billion—when Samuel Newhouse I died in 1979, according to The Nation.

The U.S. court system was apparently not too eager, however, to rule against the Newhouse Dynasty and the “Newhouse Tax Evasion Case” ended with a favorable “not guilty” verdict for the Newhouse brothers.

Yet besides owning Big Media publishing properties during the 20th-century and early 21st-century, the now-deceased S.I. Newhouse, Jr. also owned a big collection of post-World War II paintings; and in the late 1980s, he spent $17 million [equal to around $42 million in 2023] to purchase modern artist Jasper Johns’ “False Start”. And, not surprisingly, the then-owner of Jasper Johns’ modern work of art also sat on Midtown Manhattan’s Museum of Modern Art [MOMA]’s board of trustees in the early 1990s. (end of part 1)